Exploring an ancestor’s vocation as a way into the past

Until recently, the members of my particular Canadian branch of the extended King family did not know very much about the roots of our family in “the old country” that we emigrated from: namely, England. I remember my grandfather saying that he had heard we had roots in the area known as Kent, but there wasn’t a lot of certainty. After all, our family has been in Canada for 176 years. That’s a lot of generations (for my family, seven generations). It’s easy to lose track.

A great deal of legwork about the family here in this country has been accomplished by a distant cousin — the brilliant Ross King, whose work will likely be explored in future posts. Ross has traced the story of our family after the original Canadian King in our line, William “Cordwood” King, came over the Atlantic with his wife in the summer of 1853. What hasn’t been as clear, though, is just where William came from in England, what he was doing there, and who his family was.

Ross’s history makes one attempt to push back a generation into England. He writes:

William King represents the farthest reaches of our genealogical history. Little is known of William except that he married Sarah and that they had two sons, William and George, who both immigrated to Canada during the 1850s. William is also known to have been a “paper-maker” in 1853, but as Richard Hills, Director of the North Western Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester states in a letter, “One of the problems is the term paper-maker — it either refers to the owner of the mill, or sometimes the man who actually makes the paper either by hand in a vat or someone in charge of a paper making machine.”

Ross has likely got his information about William Sr. and Sarah from the marriage banns for the aforementioned George and his wife, Pamelar. (And that actually was her name! If you say it with a British accent, you’ll get it.) George and Pamelar got married in Surrey, England, in 1853. On those banns, George’s father, William Sr., is listed as a paper-maker.

Unfortunately, as Dr. Hills notes, just what “paper-maker” means isn’t always clear. Did he own the mill, or was he a worker in a mill?

We get a bit of a clue from a more recent discovery, made by another distant cousin, Kathryn Dakin, in 2016. In a local census for the village of Caistor, Kathryn discovered an entry for William Jr. that lists his birthplace as Rickmansworth in Hertfordshire. The census also shows William Jr.’s older brother, Stephen, as having been born in Rickmansworth. This bit of data is going to be extremely important.1

Caistor is the town where William Jr. and his first wife, Mary Ann Harrison, got married in 1851. We don’t know what drew William and Stephen to Caistor, which is located in the county of Lincoln, 148 miles from Rickmansworth (or about a 58-hour walk, according to Google Maps). William’s affianced, Mary Ann, was born in Lincolnshire, so presumably he met her there.

What I find interesting is the fact that, in the marriage banns for William Jr. and Mary, William Sr. is listed as a carter (essentially a kind of truck driver). To my mind, if William King Sr. was a paper-maker in 1853, but is a carter in 1851, then he is not likely going to be the “owner of a paper mill.” He’s not coming from money.

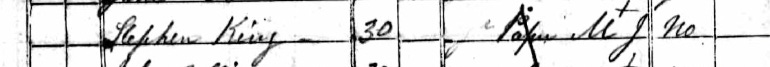

This gets some level of confirmation when we look at the Rickmansworth context. In 1841, a census for Rickmansworth lists a Stephen King of about the right age as also being a paper-maker. There are several other folks listed above and below him in the list who are also “paper-making” (or “Paper M+g”) for their occupation. Their shared abode is: Loud Water Mill House.

Loud Water Mill House was a bit of a confusing place to find (confusing for me — I’m sure at the time it was relatively simple: “Oy! Where’s Loud Water Mill House?” And then some local could tell you.) There happen to be two places called “Loud Water” relatively close to each other: one in Hertfordshire and one in Buckinghamshire. Both of them are known for their paper mills. The Hertfordshire Loudwater is our concern here.

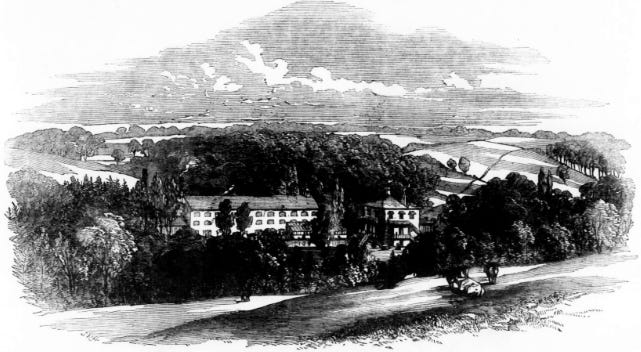

An 1851 issue of the Illustrated London News contains an extended description of the Loudwater estate near Rickmansworth, including this interesting blurb about the paper mill that we know Stephen King (my 4x-great uncle) worked at only ten years prior:

At Loudwater Mill is made much of the paper on which the ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS is printed; and in its neighbourhood may be seen Chorley Common, one of the healthiest retreats in any midland county of England, and the cedars at Chorley Wood […], not to be surpassed, unless, perhaps, at Painshill, in Surrey. Of the manner in which paper is made at Loudwater Mill, we may have occasion to speak in a future Number.

The article also includes an illustration (which makes sense, given the name of the journal):

So, all of this is just to say that paper-making shows up in our history. From all appearances, the paper-making Kings are not owners of paper mills, but rather labourers in the mills. Stephen King is the earliest instance of it that I’ve found so far, but his (and William Jr.’s) father is also listed as doing it about a decade later.

There were several jobs that fell under the category of “paper-maker”: people who gathered the cloths and rags that were used (that’s what went into the paper pulp, rather than trees, which were something of a precious commodity in England), people who cut these up, those who operated the vats, etc. We don’t know what jobs Stephen or William did, but it seems like they would have been on the factory floor somewhere.

There is probably a lot more that could be said about this paper-making backdrop for the King family. According to censuses of the time, the Kings were spending a lot of time in Hertfordshire and Kent (good call, Grandpa!), both of which have significant paper-making histories through the 18th- and 19th centuries.2 For now, maybe it suffices to say that there is a lot of value in using our ancestors’ vocations as springboards for entering more completely into the past. On Stephen’s walk to the paper mill some morning in 1841, so long ago, did he pause on the bank of the River Chess (also called the Loudwater) and wonder what texts would be printed on the paper he would produce that day?3

- I won’t go into this at this point, but as you’ll see further down, when we look at Stephen King’s appearance in the 1841 census for Rickmansworth, it actually says that he wasn’t born in Rickmansworth. Whether this has impacts on the reliability of the information about William Jr. remains to be seen. ↩︎

- Snodland History, Papermaking in Kent, and History of Papermaking in Hertfordshire and Hertfordshire Papermaking ↩︎

- This website has a fantastic description of the Loudwater Mill: “Loudwater Mill was disused as a corn mill in the 15th and later became a fulling mill. The oldest part of the mill dates from some before 1676. Paper was made there from 1747 and it was in the same ownership as Solesbridge Mill. The mill changed hands several times over the next 150 years and with each sale; the new owners added extra buildings. In 1818, Thomas Weedon, leased a field across the river where he built new industrial buildings, 14 cottages for his workers and a house, later called Glenn Chess. In the mid-19th the paper mill used new technology developed by George Tidcombe at Watford. The mill was later bought by Herbert Ingram of the Illustrated London News and later sold to William McMurray of the Royal Paper Mills at Wandsworth. He replaced the original waterwheel with the turbine which is still in situ. The mill closed when McMurray died and in 1888 the entire plant was sold. It was later converted into housing. The Old Mill House remains; a 17th or 18th building. Near it is the 19th former wheelhouse with the River Chess running beneath it, Chesswood Court, or Glen Chess. This was first built by a miller, Thomas Weedon, in 1848 for Ingram of Loudwater Mill and ‘Illustrated London News’. It is in yellow brick with a continuous veranda to ground floor with ornamental iron work and a coved roof. It was supplied with electricity by the turbine at the mill. It is now eight flats.” ↩︎