A surprising discovery reveals family in Hell, Purgatory, and even Paradise

I’ve been slowly working through Dante’s Divine Comedy. This 14th-century Italian poem has been on my reading list for a long time. Although I read Inferno about a year ago, I lost steam after finishing it, and only finally came back to Purgatorio in the last couple months.

It’s been so great.

Many readers over the centuries have recognized The Divine Comedy’s power and depth. From where I currently sit now — at this midpoint of my life — Dante’s journey has definitely been speaking to me in all sorts of ways.1

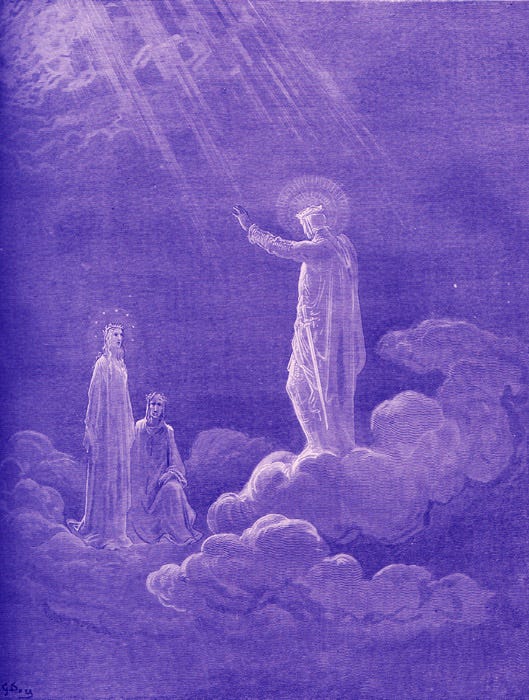

For those of you who have never read it, Dante’s Divine Comedy is a three-volume poem describing the journey of the poet Dante through hell (Inferno), purgatory (Purgatorio), and finally heaven (Paradiso), guided by his pagan poetic forebear, Virgil, the author of the Roman epic poem, the Aeneid.

To be honest, a post about Dante on my family and local history blog was not something I had remotely anticipated doing. That was before I came across this surprising passage in Canto XX of Purgatorio, though:

On yonder side they called me Hugh Capet;

Of me those Philips and those Lewises

Were born, that have ruled France this many a day. (ll. 49-51)2

The context of this passage is that Dante, during his ascent up Mount Purgatory, encounters the progenitor of a very famous set of kings: Hugh Capet. I had admittedly never heard of Hugh Capet nor of the Capetians before reading this line, but (as I have been doing many times while reading this book) I wanted to know who it was, so I flipped to the end notes to see what it had to say.

This is certainly Hugh Capet the Great, Duke of France, Burgundy, and Aquitaine […] and not his son Hugh Capet, King of France 987-96

I flipped through a few more end notes, fascinated by these figures from over a millennium ago. That’s when I came across this line in a note about lines 71-75 of the same canto:

Charles of Valois, brother of Philip the Fair

Charles of Valois… why did that sound familiar? I really can’t claim to have any actual knowledge of Italian history at all. So, it can’t be that I was remembering something I’d learnt…

I did a little digging. Born in 1270, Charles of Valois — a count ruling over several regions in the north of France — seems to have been someone who went to war a lot. A quick scan of his Wikipedia page didn’t reveal anything particularly notable other than a factoid that he served as the historical model for George R.R. Martin in developing the character of Daemon Targaryen in the Song of Ice and Fire series of books (played by Matt Smith [a.k.a. the Doctor] in the TV series). I’ve never read those books either, so that couldn’t have been it…

And then I remembered a video I made a couple years ago. It was a 45-minute long survey of my wife’s family tree, going backwards over 2,000 years. I flipped over to the slidedeck I’d made for that video and found the name around 30 slides in: Charles, Count of Valois (1270-1325). Married to Margaret of Anjou. Father of Joan of Valois.

I’d just encountered a family member while reading Purgatorio. I needed to know more.

How Do We Get There?

After some careful review, it seemed quite clear to me that Charles of Valois was a many-times-great-grandfather of my kids. How many? I wasn’t sure. That was the task. Given the several generations between Charles of Valois and my kids, I needed to know how they actually connected?

(If you aren’t a relative, you might find some of the next bit sort of boring — after all, I am going to try to move through over 800 years of family history very quickly. But, then again, you may be a family history freak like me. If so, feel free to keep reading.)

My wife’s last name growing up was Gurnett. So was her father’s and grandfather’s. The great-grandmother after whom she was named, though, was a Benner originally: Ursula Ruth. Ursula Ruth’s grandfather’s family had immigrated from Ireland around 1820. They’d lived in Ireland for just over a century, having first come from Germany at the invitation of Queen Anne in the early 1700s. (This is an intensely interesting story that I promise I will post about at some point. But not today. If you are desperate to know more now, though, this website offers a great introduction.)

We have pretty good records on the Benners and can trace them back to about 1578 or thereabouts. We don’t actually want to stick with the Benners, though. Instead we want to follow one of the matrilineal pedigrees: Ursula Ruth’s great-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Dulmage (1745-1789). Like the Benners, Elizabeth’s family also came over to Ireland from Germany during the Palatinate migration.

The Dulmage family is awesome (or “Dollmetsch” as they were previously called in Germany — a word that means “translator”). Part of what makes them so awesome is their claim to aristocracy. Many families today — maybe even most — have an aristocrat or two stuffed deep in the archives. One of the most exciting events in any genealogical search is the discovery of one of these nobles. This is mainly because of how much having an aristocrat in your lineage can open up in terms of new knowledge (more on that shortly).

Several generations prior to Elizabeth Dulmage, her great-great-great-great-great-grandpa, Konrad Dollmetsch, married a woman named Katharina Volland (1507-1550).3 Katharina’s grandmother was named Elizabeth Lyher (1442-1490). Her father appears to have been some kind of official in Wurttemberg. But her mother… she was something else.

Elizabeth von Dagersheim had her mother’s surname, not her father’s. This was because she was the illegitimate daughter of Eberhard IV, Count of Wurttemberg and his mistress, Agnes von Dagersheim.

With Elizabeth von Dagersheim — such a fun name to say — we’ve broken through a wall that looms across most genealogies. As I hinted at above, finding an aristocrat in your line is pretty exciting if you are a family historian. The thing about most people is that they just live their ordinary lives. They don’t memorialize themselves. They don’t have poems written about them. And for the most part they don’t write down where they come from unless they are forced to do so through something like a census. Sometimes in genealogy all we have as evidence that a person ever existed at all is their first name. Maybe we get a birthday or just a birth year. If we’re really, really lucky we could get a vocation.

Generally, most people live what George Eliot called “a hidden life.” That is the nature of things, and it’s probably for the good overall. It’s not great if you are doing genealogical research, though, because it means that it can be very hard to make justifiable connections between generations.

Breaking through the Wall

At any rate, Elizabeth von Dagersheim breaks through all of that and tosses things back into the open. We’ve entered the 14th century now with her father, Eberhard IV, so we’re getting close to some of the folks Dante mentions — after all, Dante lived in the 14th century too. To get a little further, though, we still need to ping pong around a bit between patrilineal and matrilineal pedigrees until we get to the Capetians, who are the main folks Dante talks about:

- Eberhard IV’s grandma was Elizabeth of Bavaria (1329-1402)

- Elizabeth of Bavaria was the daughter of Louis IV, the Holy Roman Emperor (and, incidentally, my wife’s 19-great-grandfather), and — more importantly for this post — Marguerite II, Countess of Hainault

- Marguerite II’s grandfather was Charles, Count of Valois

Discussed in lines 71-75 of Canto XX of Purgatorio, Charles of Valois played a very important, negative role in Dante’s life.

A key Italian political situation to be aware of, which lies in the backdrop of the entire Divine Comedy, is the battle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. After the defeat of the latter in 1289, the Guelphs themselves began to experience significant infighting. In the city-state of Florence, this led to a split of the Guelphs into “White” and “Black” camps.4 Dante was part of the White Guelphs; Charles of Valois was part of the Black Guelphs. While Dante was away on a diplomatic mission to Rome, Charles’s faction took over. The result was that Dante was stripped of his property and exiled for the rest of his life.

Dante’s poetry gives him no quarter.

Alone he comes, unarmed but for the spear

That Judas jousted with, and smites it clean

Through Florence, till the guts burst out of her. (ll. 73-75)

The treacherous Charles of Valois, my wife’s 21-great-grandfather, died four years after Dante, so he does not get represented as a spirit in the Divine Comedy. I think it’s clear where Dante thinks he’s headed, though.

Bad Dads

Another ancestor listed in the poem is Charles of Valois’s father-in-law, Charles II of Anjou (1254-1309) whose avarice is described starting in line 79:

Another, once shipped captive o’er the wave,

I see sell his own daughter, haggling, too,

Like any corsair with a woman-slave. (ll. 79-81)

This is a reference to the notorious story of how Charles II sold his unfortunate daughter Beatrice to Azzo VI d’Este for over $4 million in today’s dollars.5

Charles II is not the only bad dad listed in this canto. Dante also describes how Charles’s dad, Charles I of Anjou, killed many, many people, including St. Thomas Aquinas. Although it seems that the latter claim is a fairly ill-founded rumour, I did think it was cool that likely my wife’s ancestor at least knew Thomas Aquinas, even if he didn’t have him poisoned. Either way, his Wikipedia page recounts a long list of battles and killing.

The Relative Who Got into Heaven

It wasn’t all bad, though. One of the Capetians named in the poem is depicted in Paradiso. Specifically, this was Dante’s friend Charles Martel of Naples. As he encounters him in the sphere of Venus in Paradise, he describes the growing affection he feels for him, even before he realizes that it’s him (VIII, lines 46-48):

O how and how much I beheld it grow

With the new joy that superadded was

Unto its joys, as soon as I had spoken!

Charles Martel of Naples was the son of Charles II of Anjou described above. If Charles II is my wife’s 22-great-grandfather, then I believe Charles Martel would be her 21-great-granduncle. It’s nice to know somebody made it in…

The House of Lilies

I suspect many more names appearing in this canto could be tied back into my wife’s family tree — so many of them seem to be related here. As I mentioned at the beginning, the guy whose name first triggered all of this in Purgatorio was named Hugh Capet. Dorothy Sayers’s footnote says that Dante appears to be conflating two Hughs: the elder and the younger. No matter — they’re both related to us.

Hugh the Younger, who was the founder of the House of Capet and King of the Franks, was my wife’s 31-great-grandfather.6 In her book all about the Capetian dynasty, House of Lilies: The Dynasty that Made Medieval France, Justine Firnhaber-Baker writes:

On 1 June 987, Adalbero [Archbishop at Reins] crowned Hugh at Noyon, the site of Charlemagne’s coronation as king of the Franks in 768, and from there they made their way to Reims where, on 3 July, Hugh was anointed with the heavenly chrism reserved for the kings of West Francia in the cathedral where Clovis, the first Christian king of the Franks, had been baptised almost half a millennium before.

Through these ceremonies freighted with symbolism and history, Adalbero inaugurated the line of kings that would rule France for the next elevent generations, a feat unmatched by any other royal dynasty of the European Middle Ages… (9)

Dante suggests that Hugh was “the son of a Parisian butcher” who came to power after “the old kings had died out” — which is truly an awesome, almost Tolkienesque line.7 According to the actual family tree, though, it seems pretty clear that “Hugh was not even the first of his line to be crowned king of West Francia” (Firnhaber-Baker 3-4).

As usual, finding an aristocratic seam in the course of genealogical excavation is always extremely productive. Although our records get a bit sparse if we go back much further than Hugh, we still can gain a little over 100 years on his father’s line directly (going back to Robert the Strong [b. 830]). As I explore in the video I made for my wife, if we are willing to go do some more ping pong between mothers and fathers, then there are quite a few more ancient ancestors to encounter — and a lot of untapped research left to do.

On the Lookout for Relatives

There are a lot of names in the Divine Comedy and a lot of names in my family tree, so it’s quite possible that I’ve missed several others! This surprising discovery of the Capetian connection makes me look forward to the possibility of encountering other relatives in literature. It’s of course a bit weird to encounter them not only in literature, but also in heaven, hell, and in-between. (Weirder still to think of Dante as an enemy to some of my wife’s family — but also as a friend to others.)

Still, I find that this perspective gives me a way to ground some of what I’m reading in the reality that, at some point, these literary figures were living, breathing (and even bleeding) humans whose existence made possible the existence of so many people that I love today.

- The first book of the Divine Comedy opens with these words, perfectly designed for one in their mid-forties: “Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark, / For the straightforward pathway had been lost.” ↩︎

- I am reading from Dorothy Sayers’ translation of Inferno and Purgatorio. ↩︎

- If you’re keeping count, Katharina Volland is my wife’s 12-great-grandmother. We’re still about 200 years away from Dante and the Divine Comedy, which is set in 1300. ↩︎

- I did a bunch of hunting to see what the source of these names were. One guy (on Tumblr) suggested that it had to do with the colour of the hair of the leaders of the two camps. An older source suggested that it was because the wives of one of the leaders was named Bianca, which means “white,” so that camp named themselves after her. The other camp was therefore “black,” just by way of contrast. ↩︎

- This article suggests that the amount was in the order of 30,000 florins. The Wikipedia article about Azzo d’Este puts the number at closer to 51,000 florins, or over $7 million dollars today. ↩︎

- If Charles II is my wife’s 22-great-grandfather, then to get all the way to Hugh Capet requires a quick survey of several further generations: Charles II was the son of Charles I, the son of Louis VIII (called “The Lion”), the son of Philip II, the son of Louis VII, the son of Louis VI, the son of Philip I, the son of Henry I, the son of Robert II the Pious, the son of Hugh Capet (940-996). ↩︎

- Or maybe it’s better to say that Tolkien gives us a lot of Dante-esque lines? ↩︎