A short history of Edmonton’s Sky-Vue Drive-In Theatre

I am blessed to have a group of friends who love and know a lot about movies. These guys are legit cinephiles who have a ton of knowledge and affection for a medium that I also find quite interesting. I enjoy playing the role of “movie schlub” (N.B. this is a self-selected identity), while secretly learning lots and taking every opportunity to promote my favourite movie, Reign of Fire.

Recently, one of my friends informed our group chat that he had discovered something very cool: his house had been constructed on the site of one of Edmonton’s many, drive-in theatres. So cool!

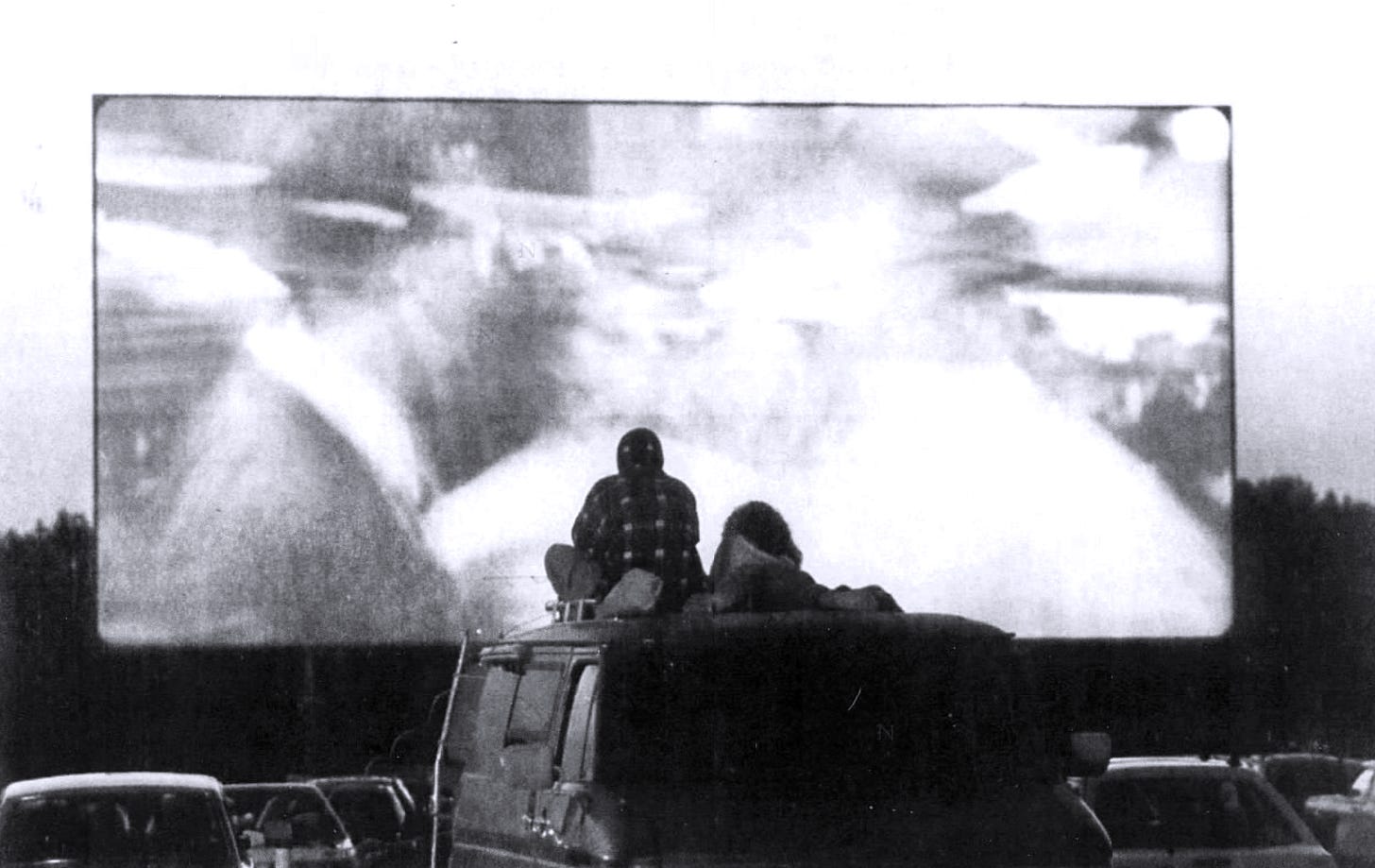

It’s been years, but I have very faint memories of going to a drive-in. I am pretty sure we went in our family’s big Dodge Ram van — the black one, with a wood panel strip and all-red interior — but I’m not really sure how we all could have see the screen from the back bench. Maybe we stood outside the vehicle and my parents just rolled the windows down?

The earliest mention I could find in an Edmonton paper of the phrase “drive-in theatre” is one in 1933 of a “theatre for motorists” that had been launched in New Jersey. The article’s bemused comment on this innovation is straightforward: “A dissatisfied audience ought to be able to register a noisy protest with horns and coughing engines.” This theatre, in fact, was the first drive-in ever and opened in June 1933 in Camden, New Jersey. The first movie shown was Wives Beware, with an admission price of 25¢.

In June 1949, the “Drive-In” came to the Edmonton area. The first drive-in theatre in the city was the Starlite Drive-In in Jasper Place, owned by Western Drive-In Theatres Limited, which had built the Chinook Drive-In in Calgary just a month earlier.1 The screen — at 55 ft wide and 47 ft tall — was the largest in Canada. Its first show was Time, The Place, and The Girl. Starlite Drive-In operated until 1971.

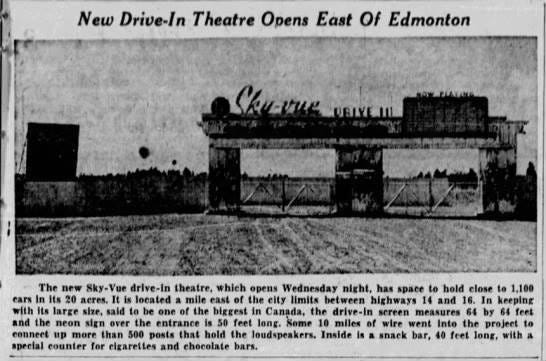

At its peak, Edmonton had the most drive-in theatres in Canada — nine altogether. (In some ways, this makes sense to me: Edmonton has always, perhaps unfortunately, been a driving city.) 1954 appears to have been a particularly active year for drive-in theatres in Edmonton, with at least three opening that summer. One of these, Sky-Vue Drive-In, had space for 1,100 cars and, at the time, was believed to be the largest in Canada.

My friend’s house is built on the site of the former Sky-Vue Drive-In.

Sky-Vue Drive-In

The first showing at the Sky-Vue was Blackbeard the Pirate, which occurred on Wednesday, July 8, 1953. It was set to start at 9pm. Coincidentally, sunset on July 8, 1953, happened at 9:08pm. I’m sure those first 8 minutes were a little bit irritating.

In the Edmonton Journal for that day, there is a full page devoted to the theatre’s opening, including (somewhat bizarrely) a series of “congratulations” ads from the different contractors involved in the theatre’s construction. This includes:

- Cheshire Construction, which completed the concrete block-work

- Carey Decorators, which did the painting and decorating

- H.E. Cockroft, who did all the carpentry work “including the snack bar”

- Edmonton Supply Company, which provided all of the plumbing, fencing, and speaker posts

- Niagara Power Electric, which did all of the electrical installations

- Beaver Construction, which supplied the crushed gravel

- Kilbride Roofing, which roofed the snack bar and other buildings

- Ikar Concrete Construction, which did all the concrete work for “the foundation for the screen and the entire floor of the snack bar” (emphasis mine)

- Dominion Sound Equipments Ltd., which supplied and installed the sound and projection equipment

- E. Traub, who erected the fence (and whose company tagline is, “fences of all types erected anywhere”)

- Clem’s Welding, which presumably did the welding. I am not sure whether they were involved in the snack bar, which sounds epic.

In fact, the snack bar gets a special call-out in the newspaper article:

The drive-in features a 40-foot-long snack bar with a special counter nearby for the sale of cigarettes and chocolate bars. The idea of the special cigarette counter is to ease the pressure off the snack bar, that features a wide variety of foods and drinks, in the rush periods that come during intermissions.

It takes a village to build a 40-foot-long snack bar apparently.

(I am actually quite intrigued by the calling out of all of the different trades involved in the construction of the drive-in. It is almost like a kind of “credits” roll.2 It would be interesting to look into the different companies and see which ones, if any, are still around.)

Sky-Vue Drive-In also didn’t just show movies. Over the coming years, it played host to giant bingo events (with tickets at $10/car), sunrise Easter Services (organized by the Lutheran churches, featuring a mass choir and “a group of trumpeters”), and also just a smidge of controversy.

In 1973, several parents in the Ottewell area circulated a petition to pressure the theatre from showing three restricted films, The Oldest Profession (featuring Raquel Welch), Miracle of Love, and Without a Stitch. Without a Stitch had been subject to obscenity trials in Europe. One person interviewed in a June 1973 article in the Edmonton Journal reported that “the movie stopped traffic on 58th Street.” (In fact, according to the district manager of Odeon Theatres, which ran Sky-Vue at the time, “Attendance [at the films] had been ‘very good’”). The petition went all the way up to Premier Peter Lougheed, after which the theatre bowed to the community pressure and withdrew the films. The same year as the petition, an armed robbery occurred at Sky-Vue. The robbery netted $210 (about $1500 in today’s dollars).

The last films at Sky-Vue were shown on November 30, 1975: Juggernaut, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, and Hang ‘em High. Over the years, it was first independently owned (until 1961), then owned by Odeon Theatres until 1974, and then owned by Landmark Theatres until its closure. In 1976, a notice appeared in the Journal advertising a public meeting to inform the Ottewell residents about the planned development on the Sky-Vue site.

By the 1980s, the appeal of the drive-in was on the decline — and not just in Edmonton. The last drive-in to close in the city was the Twin Drive-In in 1997. Currently, there are about 40 drive-ins left in Canada, down from nearly 250 at its peak.

The first drive-in theatre in Canada appears to have opened in 1946 in Stoney Creek, Ontario (near Hamilton). The Edmonton Journal article describing that venue ended up being unwittingly prophetic:

We can imagine the family of the future stepping into the car, which will be in a built-in garage, speeding off to a drive-in restaurant, moving on to a drive-in theatre, and returning home without once leaving their seats in the automobile.

Haha, like that will ever happen!

- Western Drive-In Theatres Limited is an interesting company that bears a bit of a closer look. It was founded by five entrepreneurs in Calgary and led by Mervyn “Red” Dutton, a former hockey player and coach who played in the early years of the NHL. Often Western Drive-In would use Dutton’s other company Standard Gravel and Surface Limited to complete its projects. Standard Gravel went on to become the company known today as Standard General. Other partners in the Western Drive-In venture included J. Ross Henderson, a chartered accountant in Calgary, The manager of the drive-in theatre construction was a former silent movie theatre manager named Frank Kershaw. According to this fantastic zine from Calgary’s The Sprawl, Kershaw died tragically in the Tenerife Airport Disaster in 1977, one of the worst aircraft disasters in history. ↩︎

- Admittedly, the practice of including an end credits roll was not common in North America until the 1960s. ↩︎