An Event, Perhaps:A Biography of Jacques Derrida

by Peter Salmon

Publisher: Verso Books (October 2020)

Pages: 320

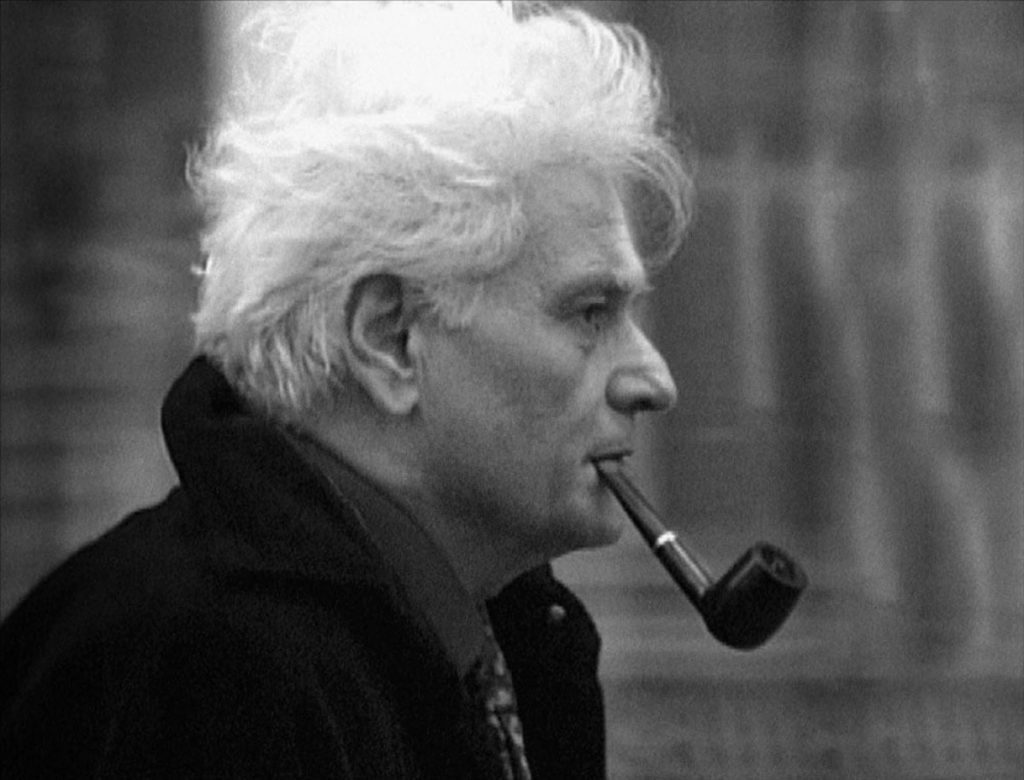

I still remember the year Jacques Derrida died. I was taking a fourth-year continental philosophy class with some friends, and I don’t recall if we were reading Derrida at the time, but he was all over the texts and our prof took it hard. I had grown fond of him myself by then (despite having more of a “feel” for Derrida than any sort of deep engagement with his work). When Pope John Paul II died a few months later, my friend reflected on the two losses: “There go the last two Christians in the world.” (I’m still not entirely sure what he meant by it, but it felt true at the time.)

It’s been over 20 years since Derrida’s death and over 10 years since I defended my PhD thesis. Admittedly, with a couple of exceptions, I have not really gone back to any of the “theory” that fascinated me for so many years through undergrad and graduate school. I still have many of these titles on my bookshelves. Gilles Deleuze. Jean-Luc Nancy. Michel Foucault. And, of course, (always-already) Jacques Derrida. Yet I know that the traces of their thought remain.

Reading this wonderful biography of Derrida’s life and thought brought it all back to me.

The author, Peter Salmon, is upfront about the choices he faces at the outset of embarking upon a biography of the “father” of deconstruction. He can go the route of so many Derrideans and others in his wake, punning and playing like a riverrunning James Joyce hopped up on speed, and likely failing miserably to get anywhere close to what Derrida himself was able to do. Or he can forgo the obscurity and make an attempt at clarity. Thankfully, he chooses the latter option.

As a result, Salmon succeeds in bringing sharply into focus the urgency of Derrida’s entire project both for its time and today. Again and again, I was reminded of the ways that Derrida — or at least university classes and texts we read for those classes or that I used in my thesis — influenced my thinking. And I was filled with gratitude for that influence.

I have sometimes looked back on my time in school and regretted my obsession with theory. I still remember my first Theory prof, Dr. Karyn Ball, in my second year, telling us how “seductive” theory could be. Of course, it’s obvious that even just saying that theory is seductive is seductive to a young person, freshly out in the world, dying to form their own opinions, desperate to engage and wrestle with ideas and history and the human condition.

I came fully ready to be seduced.

But in the ten years since my PhD, which was in English Literature, but had a major focus on “theory and criticism” (my secondary comprehensive exam was focused on texts from that area), I have often wondered if it was a waste of time. Instead of wasting my time struggling through texts I just barely understood (or not at all), I could have really learned about literature. I could have finished all most course readings. I could have taken a secondary reading list in 18th-century literature or modernist literature and really gained a more expansive sense of literary history.

Some of those regrets still linger, but this book has stilled them for a moment and reminded me instead of the beauty of ambivalence, of the equivocal, of the impossible, of traces, différance, and above all deconstruction. It has reminded me that, actually, when I first encountered theory — and especially when I began to encounter this hesitant, uncertain, humble (at least in some of its forms) way of approaching the world — it was not so much that I had all of my existing beliefs and thoughts turned upside down. Rather, I felt like I had finally found some words to express the way the world already seemed to me to be.

The people who were so certain that things were this way, or that things had to be that way: I loved them, but I couldn’t quite grasp how they got there. It’s not that I didn’t act certain about things: I did. The reason I did, though, I knew in my heart of hearts to be because of fear. I needed to act certain or say things in confident ways or police the ideas of others because deep down I was nervous that God would be angry or (even worse) that someone I loved in my community would be angry and reject me. But I wasn’t actually certain about much. I couldn’t be.

Entre Derrida.

Salmon’s biography seems to cover the bulk of Derrida’s major works. It is chronological, but not in a straightforward way, which keeps things interesting. He will spend long passages unpacking a concept in Husserl and then shift beautifully to a biographical moment that, even if it doesn’t always image the concept anecdotally, reminds us that these men (and a few women) cared about the relationship between ideas and real, lived experience. Perhaps none more so than Jacques Derrida.

One of the things I loved most about the book was how much it got me excited to open some of the volumes I’ve had on my shelves for years unread. Reading of Derrida’s affection for Levinas, I kept standing up and going over to my copy of Totality and Infinity, which I first picked up for the Honours seminar I took with Dr. Chris Bracken — one of the most formidable and inspiring teachers I ever had and a brilliant, 100% dyed-in-the-wool theory-head.

“The true life is absent,” Levinas starts with — quoting from Rimbaud, “but we are in the world.” Here is a first philosophy worth getting behind. To be in the world (and, perhaps, not “of it”) requires a method for remembering where we are. Deconstruction can be a way of doing that — or, to put it in another way, of working out one’s salvation in fear and trembling.

The biography perhaps could have gone into more detail on the facts and narrative of Derrida’s life story, but in the end that didn’t matter to me. I mostly just closed the pages feeling grateful and inspired to take up the project again.