The History of a Forest that became a River Lot, that became a Farm, that became an Edmonton Community

My family has had roots in the Gold Bar neighbourhood of Edmonton going back over fifty years. My grandparents lived in the area, and my parents currently live there. The church that our family is part of currently meets there as well. My wife and I have served on the board of a school that has been located in the area since the early 1970s.

I recently made a small booklet and poster for my parents describing the history of their house and the neighbourhood of which it is a part. That latter section, which focuses on the history of the Gold Bar district, seems like it might have wider interest for folks who have either lived there or been part of the community in other ways.

A new neighbourhood for $2000 an acre

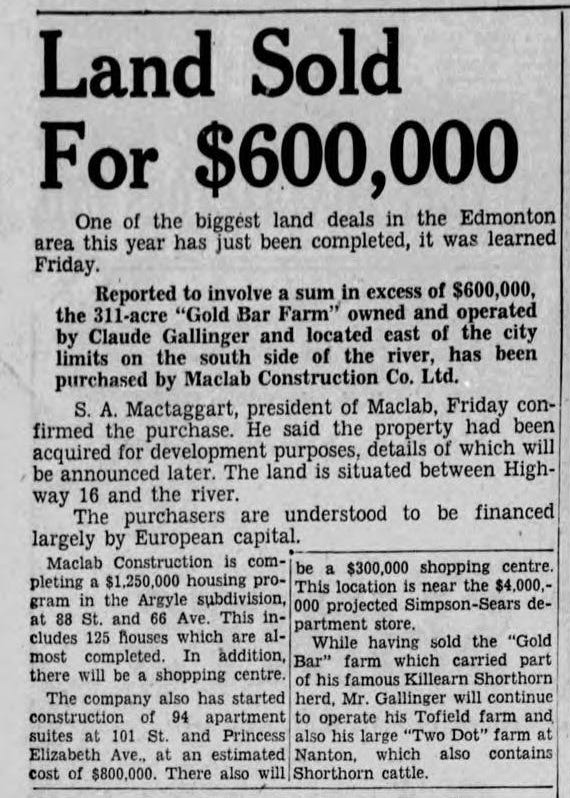

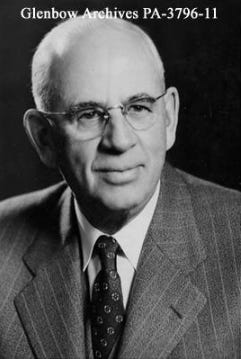

The Gold Bar neighbourhood — as such — got its start as a result of the $600,000 purchase in 1955 of 311 acres by Maclab Construction Ltd. Maclab was a firm owned by two wealthy friends, S.A. MacTaggart and Jean de la Bruyère. (The company name combines their two names: “Mac” from MacTaggart and “Lab” from LA B-ruyère).

Upon purchasing this land, the farmyard itself, known as Gold Bar Farm, was subdivided out of the parcel and retained by Jean de la Bruyère as his personal residence. It remained in his family until 2022.

Maclab construction built many of the houses in the new subdivision, as it also had done a few years earlier in the Argyll neighbourhood around 88 Street and 66 Avenue. Other home builders in the area included McConnell Construction, which had a show home at 104A Avenue and 50 Street.

Shorthorn on the Saskatchewan

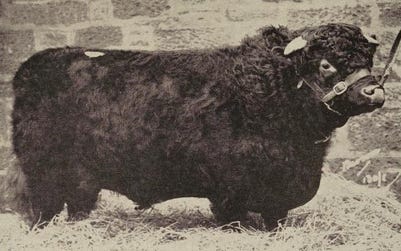

Prior to Maclab’s development, which was further facilitated by the annexation of the Gold Bar district into the City of Edmonton in 1956, the whole area had served as farmland for many decades. Claude Gallinger, the successful cattleman who had used the land to raise Killearn Shorthorn cattle for two decades until he sold it to Maclab, was born in 1881 in Lanark, ON.

In addition to his land in Gold Bar, he also had farms in Tofield and Nanton. Gallinger eventually joined forces with two other powerful men in the Edmonton area to establish Crafts, Lee, and Gallinger, a large real estate and coal company. (The “Lee” in this partnership was Robert Lee, former mayor of Edmonton).

Clearing 100,000 feet of lumber

Although Gallinger’s cattle had been a sight on the land for many years, he was not responsible for clearing the land nor for building the original homestead, which still stands to this day on the crest of the hill at 106 Avenue and 46 Street. D.W. Warner, who purchased the land in 1899, upon his arrival in Edmonton, reputedly cleared 100,000 feet of lumber from the land and built the brick homestead in 1913: Gold Bar Farm. Local lore says that the name comes from early prospectors in the area who would pan for gold in the shallows of the river on the banks along the north edge of the river lot.

Warner was active in politics, including serving as president of the Alberta Farmers Association (a precursor to the powerful UFA, in which he was also involved). Warner was born in 1857 in Keokuk County, Iowa. At Gold Bar, he grew a variety of crops and raised both cattle and hogs.

During Warner’s ownership of the Gold Bar Farm land, a venture was attempted to establish a fashionable housing district known as the Hollywood subdivision. This got its start through the efforts of the Morris family, which owned land immediately to the west of Gold Bar, and a company called Western Canada Properties Ltd. The original development plans proposed wide boulevards and classy, tree-lined streets, with an institute to be called Alberta College just to the east. This was not to be, though, as Edmonton (along with the rest of the world) experienced a significant economic downturn during the years that followed. War was declared in 1914.

The blacksmith’s son and River Lot 39

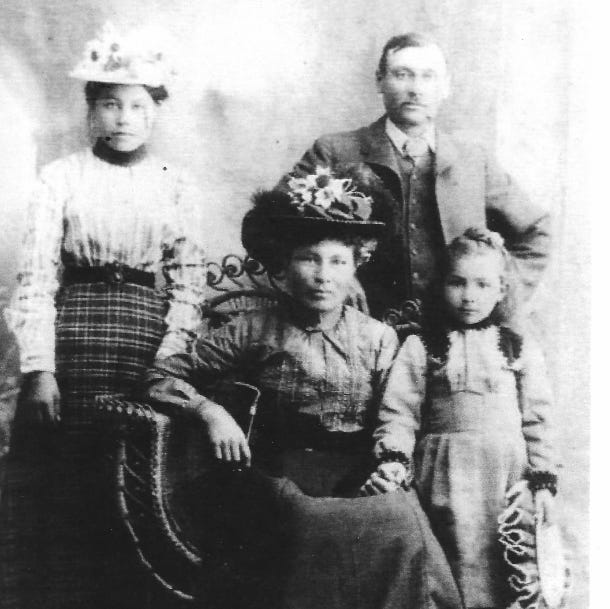

Prior to its homesteading and development by D.W. Warner, the Gold Bar district, in the middle of which now stands the bi-level house 4904-104A Ave, was known as River Lot 39. By 1883, there are maps that show the lot to be owned by John Borwick, a Métis employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Records show that Borwick claimed occupancy of the land as far back as 1881.

John Borwick was born in Fort Edmonton in 1863. His father, William Borwick, who came from the Orkney Islands in Scotland, served as one of Fort Edmonton’s blacksmiths. He owned a river lot on the other side of the North Saskatchewan River (in the area of what is currently Concordia University of Edmonton).

John married another Métis person named Eliza Erasmus in 1885, who was the daughter of Peter Erasmus Jr., the famous translator and guide who accompanied Palliser on his 1857 expedition and co-wrote Buffalo Days and Nights. (Erasmus’s Danish father had apparently fought in the Battle of Waterloo.) Borwick served as an army scout during the 1885 North-West Resistance. He went on to help found the community of Andrew, Alberta in 1900. Eliza was the town’s first postmaster.

The river lots along the North Saskatchewan River weren’t formally surveyed until 1882. In keeping with their Québécois origins, river lots were intended to be approximately one-mile long. Because of the curve of the river, Borwick’s land was almost 1.5 miles long (116.12 chains, which was the unit of measurement for surveying).

Prior to the 1880s, there would likely have been a variety of users of the land (both settler and Indigenous), although there does not appear to be evidence of specific “improvements” at this early point, such as exist on the land of Philip Tate, Borwick’s neighbour (and uncle) to the east who later served as the chief factor of the Hudson Bay Company’s Victoria Post. For the most part, maps of the period show that it consists of forest — from the dirt road that later became Highway 16 and then still later 101 Street up to the shores of the 12,000-year-old river that the Cree people called kisiskâciwanisîpiy.

There is not much written information available on the land prior to its surveying, although the region is known to have been the traditional territories of the Plains Cree and Blackfoot people.