My Victorian ancestors were about as Victorian as you can get

This post was originally going to be a tiny little section at the tail-end of the deep dive into William Wem’s experiences in World War 1. What was Frances Wem, his wife, up to during the years she lived in England with her children? In the course of researching this, though, I uncovered some truly bizarre factoids that deserved a post all of their own.

During much of the time that William Wem spent in the army over the course of World War I, William’s wife Frances is listed in William’s military “separation” payment forms as being located at 16 High Street in Brierley Hill. The building is one that no longer exists.1 At the time, it was located a stone’s throw from both St. Michael’s Church — just to the north — and St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church — to the east.

Initially as I was preparing this post, I had thought (and think I may have indicated as much in my previous post) that this address was in fact where Frances Wem and her family (and possibly her mother, who was born in Brierley Hill and who lived with the Wems before they emigrated to Canada) resided during their time in England.

I found some directories from the time in question. Bennett’s Business Directory for Staffordshire in 1914 indicates that there was a grocer, H. Severn, located at 15 High Street in the town. Another grocer (and also confectioner), J. Cox, was located next door at 18 High Street. The 1912 Kelly’s Directory of Staffordshire shows the offices of several members of the Urban District Council as located at 17 High Street.

For the above reasons, I think that it seems quite unlikely that “16 High Street” is the residence of Frances Wem and her family. Instead, I am suspecting that this is the location of the post office, which Kelly’s Directory lists as also being located on High Street (although it neglects to give its full address).

So where did Frances stay while she and the girls were in England? One possible avenue for investigation is a listing also in Kelly’s Directory for someone named “James Thomas Randle”. Randle was the maiden name of Francis Wem’s mother.

James Thomas Randle, who appears to have sold musical instruments in the market buildings in Brierley Hill and was at one point listed as an organist, was born in 1889 in Kingswinford, where several other Randles in my family are from. Although it is tempting to list the most interesting fact about James as being that his wife’s name was Alice Cooper (it really was!), more to the point (and contributing to a truly much more wild fact) is that his father was named Charles Randle. Likewise, Frances Wem’s grandfather’s name was Charles Randle. Were these two related — uncle and niece, maybe?

This is where things get wild.

A quick sidenote on genealogical research. Most of us who do this are just doing it off the side of our desks. It’s a passion; it’s an obsession; etc. Nowadays, the tools at our fingertips are remarkable. Previous generations had to do the physical work of visiting archives and church basements, writing away to small county libraries, etc. There was a built-in cautiousness necessary to the work. Today, a subscription to Ancestry.com (or *.ca, which is what I use) gives one greater access to the past than anyone has ever had previously. This facility does sometimes lead to mistakes. Although there is a culture in genealogical circles that presses for good sourcing of names, dates, etc., the experience of coming across an ancestor that you’ve been looking for for years and encountering the possibility that you might finally break through a “brick wall” can be so tantalizing that it is understandable for researchers to sometimes add a name without sufficient evidence.

I thought something like this had happened as I tried to track down a potential relationship between James Thomas Randle and my great-great grandmother, Ann Elizabeth Lloyd (née Randle), Frances’s mother. Both of these people list their father as “Charles Randle,” with very similar birth and death dates, and also the same vocation, namely, blacksmith. The problem I was running into was that my record for Ann Elizabeth shows her mother as Susanna while James Thomas shows his mother as Margaret. Yet both women were still living. Divorce in the 1850s was also still pretty rare, so this seemed unlikely.

One of the family trees I came across made the bizarre claim that it was an example of bigamy! When I saw this claim, I just laughed because it’s the sort of thing that some less-rigorous genealogists will sometimes claim in order to deal with contradictory evidence. It’s an easy-out and usually just silly: “It’s not my evidence that’s wrong; it’s the moral situation of the ancestors — it must be bigamy!”

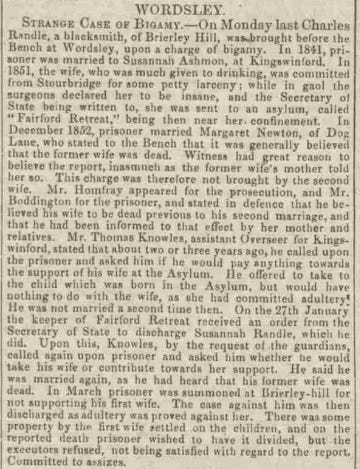

So I dismissed this claim and hunted around to see if maybe the very similar Charleses were just competing blacksmith cousins or, more likely, if maybe I had got one of the mothers wrong. But then I came across this article (via a relative on Ancestry) in the Worcestershire Chronicle & Provincial Railway Gazette for May 17, 1854 (which I am reproducing in full because it is a doozy — in case you don’t want to read it all, the summary is below):

The short version is that my great-great-great grandfather, Charles Randle, is both the father of Ann Elizabeth AND of James Thomas by two different women: Susannah Randle (née Radford, and then Ashmon/Ashman from her first marriage) and Margaret Randle (née Newton). That sort of thing may not be unique in itself. What is perhaps a bit more unique and surprising is that Charles was married to both of these women at the same time.

And the reason he got married twice is about the most Victorian reason you can imagine. Seriously: his first wife went insane, got bundled away to an asylum, and then he went and found a second wife, thinking (or claiming to think) that his first wife had died there. There are many, many, many Victorian novels (as well as many real-life Victorian / 19th century examples) of women being locked up in asylums. (Jane Eyre, which doesn’t technically involve a wife being locked in an asylum, but does involve bigamy, was published in 1847 — just four years before Susannah Randle was committed). In this case, Susannah Randle was committed to an asylum that was perhaps not quite as bad as the ones in the books.

The Fairford Retreat

Asylums during the Victorian period were not generally nice places. It was interesting, therefore, to read about the asylum my great-great-great-grandmother was committed to, which the above article calls, “The Fairford Retreat,” but more generally was just called “The Retreat.” It was founded by Alexander Iles in 1822 and, until 1859, took in “pauper patients.” (After 1859, government policy changed to require these patients to be admitted to the County Asylum, which did not appear to exist prior to this year.) In 1851, the year that Susannah Randle came to the Retreat, there were 200 other patients housed at the Retreat. The philosophy of the Retreat was one of non-restraint and humane treatment, which was relieving to read.

Susannah’s actions during this time — drinking, petty larceny, and adultery — and the decision by the doctors at the time that she should be committed to the Retreat suggest that she was suffering from severe mental illness. It is not clear how Charles came to believe that she had died while she was living in the asylum — the article says that he heard this from her mother (Anne Radford [née Brooks]); however, there were many deaths at the Retreat, so it is perhaps not surprising that Charles thought this. In fact, the article linked to above suggests that a third of all patients died.

The Many Children of Charles Randle

I was curious to know what happened after this “strange case” concluded. The article was published in 1854. If we look at the next census record in England, which was for 1861, Charles is still listed as a blacksmith and as living with his second wife, Margaret. With them are 5 children — Joseph Randle (14) and Elizabeth Randle (12), who are Charles’s children with Susannah, and then John W. Randle (4), Charles H. Randle (2), and Alfred Randle (5 months), who are his children with Margaret. The census also lists a boarder, Richard Ashman (22). Richard is Susannah’s son from her first marriage. It was good to read that he was being taken care of, despite everything that had happened.

If we go back ten years to the 1851 census, which shows Charles as still being with Susannah, there are a few curious differences. This time, the children listed are: Richard Randle (12), William Randle (6), Joseph Randle (4), Ann Randle (2), and Jane Randle (1). There is no difference for Joseph and Ann besides them being ten years younger (and Ann going by her second name in the 1861 census). With the other kids listed, though, there are a few questions:

- It is not clear whether the “Jane” listed here is the child born out of wedlock mentioned above in the article, although the dates do not seem to line up properly to make this the case. Jane is born in 1850, and Susannah appears to not be in the asylum until 1851. It is also not clear where Jane Randle is in 1861.2

- Richard in 1851 goes by the surname of his stepfather, Randle, but reverts to the surname of his birth, Ashman, ten years later. Whose decision this was — whether Richard’s or perhaps Charles’s — we can’t know.

- Finally, William Randle, who should be 16 in 1861 does not appear at all. Although it is not conclusive, it is perhaps noteworthy that a William Randle, aged 8, is listed in a different record as having died in Brierley Hill on October 28, 1853.

The 1871 census shows Charles’s children with Margaret: John W. Randle (24), Alfred Randle (20), our organist granduncle James Taylor Randle (18), Frederick Randle (16), George Randle (12), Emily M. Randle (10), and Henry Randle (7). Charles and Margaret’s family expands. Joseph and Ann are both out of the home—by 1871, Joseph is married and working as a victualler (and, later, a Professor of Music) and Ann has married a shoemaker (my great-great grandfather, James Lloyd). Meanwhile, Jane reappears on the scene and is living as an assistant in a home in Warwickshire. Finally, Richard Ashman, now 32, has moved on and is living in Australia, having gotten married in 1868. He dies there in 1908.

Oh! Susannah

My ancestor, Susannah Randle, does not wholly disappear from the historical record. On March 6, 1871, there is an entry in the Worcester Assizes that shows her as being charged and sentenced to 14 days in jail for another instance of larceny. There is an entry in one person’s family tree (and substantiated here) that suggests that Susannah enters the Stafford Asylum in Staffordshire on June 19, 1877 and is ultimately released 5 months later. She would have been 57 years old.

After that, it’s not clear where she goes.

- It would be very interesting to know why the building no longer exists. Although it appears to have been secure during the Great War, it is notable that this area was — particularly due to the proximity of the salt colliers — later in Hitler’s sights and was a target. There was, in fact, at least one fatality listed in Brierley Hill as a result of the Blitz. ↩︎

- We get some insight, though about Jane Randle’s whereabouts from the 1871 census. There we learn that she is living still under the name of Jane Randle as an assistant for people named John and Susannah Husselby. ↩︎