On July 1, 1915, mere days after the biggest flood in Edmonton’s history swept over his family’s home, William Wem signed up to join the 66th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. He was 44 years old.

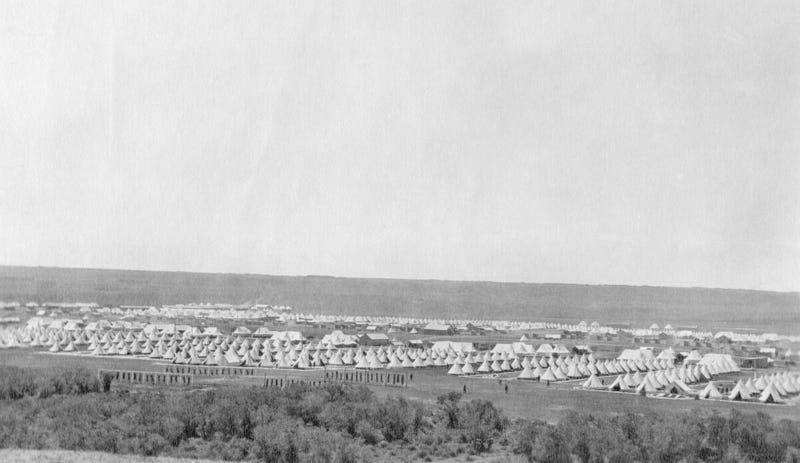

From August to October 1915, the 66th Battalion resided in Camp Sarcee in Calgary, Alberta, where it underwent training. In October, William and his fellow troops returned to Edmonton, where they were quartered in the City Park Barracks next to the Edmonton Exhibition Grounds. There were approximately 1,070 soldiers in the battalion. Over the next few months, troops were kept busy with training, marches, and many athletic competitions, about which the Edmonton Journal notes:

With the exception of hockey, at which game the battalion did not excel, the 66th battalion was never beaten in any athletic games or competitions. (April 21, 1916, p. 11)

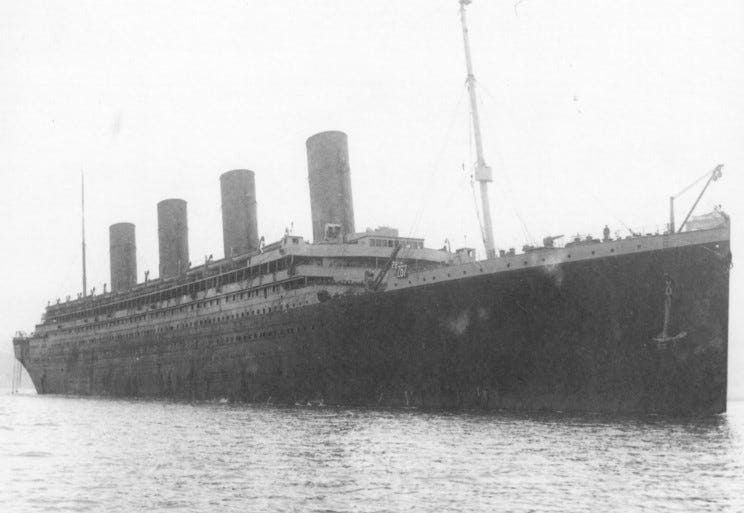

The 66th Battalion left Edmonton on April 21, 1916 aboard two special Grand Trunk Pacific trains. After a stop to be inspected by the Governor-General in Ottawa, the troops embarked upon the S.S. Olympic on April 28, 1916, bound for Liverpool. The ship set sail May 1, 1916 and arrived in England on May 7. (I did not realize that the transatlantic trip was so quick — apparently this was due to the invention of steam turbines.) Troops were subsequently moved to be stationed at Shorncliffe Army Camp in Kent, near the port at Folkestone, on the banks of the English Channel. They remained here until June 26, 1916.

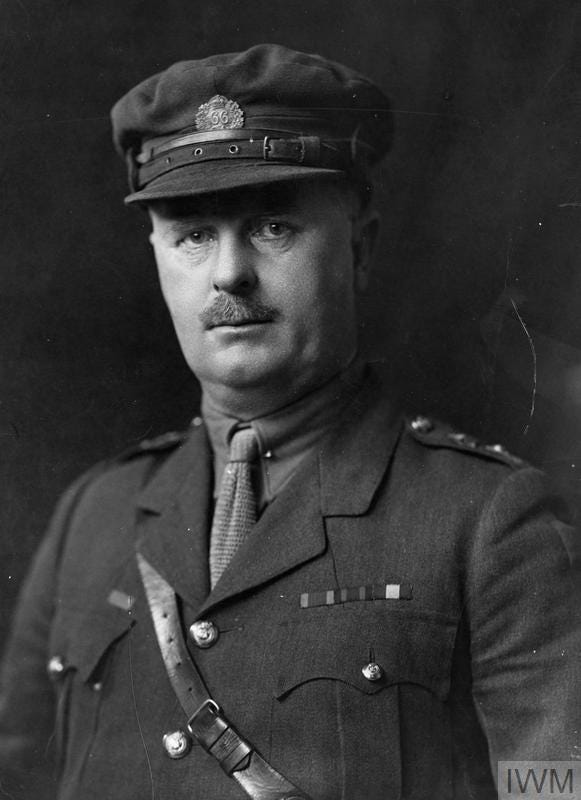

The 66th Battalion was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel J.W.H. McKinery.

William joins the C.A.S.C.

On June 26, 1916, William left England to join the fray. He disembarked at Le Havre in France. William was transferred out of the 66th Battalion — most members of this battalion were moved into other units upon arrival in Europe — and “taken on strength” (which means that he transferred into another unit) into the Canadian Army Services Corps (C.A.S.C.). By July 20, he had joined the No. 9 Depot Unit of Supply within the C.A.S.C. This unit was under the command of Lieutenant W. M. Copeland.

The C.A.S.C. was composed of numerous units, including the Depot Units of Supply (D.U.o.S.).1 Each D.U.o.S. contained approximately 30 people. They were responsible for unloading supplies from ships and distributing these onto the trains that carried the supplies out to the troops. The supplies included food, equipment, military supplies, clothing, and other material. These personnel also had responsibilities relating to the repair of vehicles and also often would be responsible for driving vehicles.

Between July 20, 1916 and October 6, 1917, it is not clear what William’s activities included, although it is clear that he belonged to the No. 9 D.U.o.S. during this entire period. Our family has stories that William served as a stretcher bearer in the war. It is unclear whether this was officially a task undertaken by members of the D.U.o.S. This document lists stretcher bearers among the Canadian Army Medical Corps (C.A.M.C.), but is careful to note that they were not, strictly speaking, C.A.M.C. personnel. There were 16 stretcher bearers per battalion, trained by the Regimental Medical Officers (R.M.O.). One document I came across noted that the role of stretcher bearer was often filled by German prisoners-of-war, which suggests that it may not have been the safest of jobs.

There are apparently Daily Orders available that may provide additional insight into William’s movements during the war. Unfortunately, these appear to be largely in Ottawa at Library and Archives Canada.

William’s Casualty Form does list a handful of events over the 3 remaining years he is overseas:

- On October 6, 1917, he is granted a leave of absence. He rejoins service October 13, 1917. We don’t know what he does during this time away. Notably, this was around the time that Canadian forces entered the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), in which many Canadians fought and were injured or killed (including my own great-great uncle, Gordon Suddaby, who died November 10, 1917). I wonder whether the horrors of this battle led to him needing to take leave. October 6 is just a couple of days after the end of the Battle of Polygon, which saw more than 15,000 casualties.

- On August 5, 1918, he is classified as “B2” by the Medical Board, with the cause listed as: “aged. v[aricose] veins.” Classification B2 limited the service that William was permitted to take part in although it did allow him to continue working in the C.A.S.C. According to Jordan Chase, this classification exercise was part of a widespread decision at the time (completed on August 12, 1918) to update the classifications of soldiers in C.A.S.C. units in order “to ensure that any troops fit for frontline service were transferred to infantry units. The idea was that these individuals were of more use in combat units, and their experience and expertise along the lines of communication could be more easily replaced” (p. 270).

- On October 13, 1918, William is granted 14 days leave to the U.K. Since his prior leave of absence request does not indicate that he is permitted to go to the U.K., it is possible that he remained in France during his leave the previous year. He rejoined service on October 27, 1918. (Incidentally, 89 years before my second daughter was born). I do not know if letters between Frances and William exist. If they did, perhaps they would include information about the reason for this return to the U.K. With the end of the war only a month away, perhaps William was returning to help Frances with preparations for the family’s return to Canada, which occurred in early 1919.2

The next record on the Casualty Form is dated November 20, 1918, which shows William as being struck off service (“S.O.S.” — meaning “removed from a unit”) from the 9th D.U.o.S. as of November 10, 1918 and joining the 8th D.U.o.S. He is then S.O.S. from the 8th D.U.o.S. on November 11, 1918 and rejoined the 9th D.U.o.S. It is not clear what is happening here; however, it must be related to the end of the war, which occurred on November 11, 1918.

Somewhat infamously, the Canadian Forces had trouble getting back home following the end of the war. (Hat-tip to my cousin Carissa for pointing me here to the events surrounding the riot at Kinmel Park). These delays related to a perfect storm of competing shipping interests, labour strikes, and the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu, the last of which swept the globe (and which caught up with William in March 1919, further delaying his departure).

It is somewhat remarkable to read that the end of World War I occurred in November 1918, but that William was not able to get home until late June 1919 (and, in fact, it seems doubtful that he would have arrived home prior to July 1919, given the time it would take just to get across the country). Seven months on top of having already been apart from his family for 3 and a half years of fighting — it boggles the mind. With all this in mind, it is perhaps not surprising that Canadian soldiers rioted.

Nevertheless, William was not involved in the riot. We can know this for a few reasons, including that he was, at the time of the riot in March 1919, in a Medical Depot being treated for influenza. Another reason is that it seems that, as of March, William was still somehow not back in England. Although his records show him as being at Kinmel Park after the war, this was not until late May 1919.

Instead, William is cited as having “returned from field” and arriving at Blandford Camp (in south England) on April 28, 1919, following his recovery from the Spanish Flu. He remains here until May 20, when he is transferred to Kinmel Park (near Rhyl in Wales). While in Kinmel Park, he is admitted to hospital for treatment for laryngtis.

As I read about these last three or four months of William’s time in the military, I just keep thinking: “Get this guy out of there!”

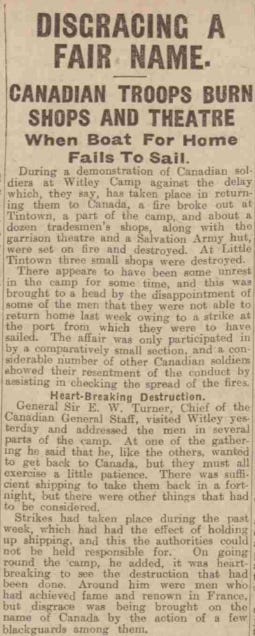

For some strange reason, upon William’s recuperation from laryngitis, he moved one more time from Kinmel Park in Wales to Witley Camp in Surrey, England, arriving June 2, 1919. Interestingly, although William was not present during the Kinmel Park riots, there was also a riot at Witley Camp on June 14, 1919. It appears that this was driven less by the delays in demobilization and more by shopowners charging unjust prices to Canadians (to such an extent that soldiers would ask British soldiers and local residents to purchase goods on their behalf). William would definitely have been on site when this riot took place; however, it is not clear how extensive the riot was.

Finally, on June 26, 1919, nearly four years after William signed up to joined armed service, and three years to the day after he disembarked on French soil, he was discharged to Canada. He was 48 years old when he arrived home, ready to begin the rest of his life. A year later — in fact, a year to the day of his discharge from the army — his daughter Kay was born.

- This is a great post about the Depot Units of Supply: “In 1914, a Depot Unit of Supply consisted of one officer and thirteen NCOs and men, and five were provided for each division. They were units of the Army Service Corps. Most supplies were shipped to France (and other theatres) in bulk, and transported forward by rail to places called regulating stations. At these, the bulk supplies were split up into divisional trainloads for daily transport forward to the men in the front line. It was at this point that the Depot Units of Supply came in: think of them basically as a team of warehousemen, collecting their division’s ‘share’ from the bulk supplies and arranging for it to be carried forward. Eventually these units were grouped into Lines of Communication (L of C) Supply Companies for ease of administration, and functioned from Base Supply Depots (BSDs).” ↩︎

- It is also possible that these two weeks were part of the initiative described here: “Upon the recommendation of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in France were given two weeks’ leave in England to visit family and friends, after which they would reassemble for transport home.” ↩︎