A brief detailed chronicle of our minute-by-minute dislocation

This entry — long overdue — tracks some of the ways that we find ourselves unsettled from a creaturely way of life even in just the first few minutes of an average day. My hope is that it will also uncover counter-movements and signs of what Charles Taylor calls “fullness” at work all around that are sometimes hard to see.

When it comes to waking up, I almost always beat my clock. The night before, I dutifully set my alarm, calculating how much time I will need the next day to get ready and be where I need to be and by what time. Yet I always wake up before the alarm can start shrieking. My body just seems to know. It’s 6:44am: wake up, turn off the alarm. If you don’t, you’ll get the shriek.

I awaken to darkness, but not only darkness. There are also usually the sounds of various appliances: our furnace, rumbling away; further away in the distance (since we sleep in our basement), I can hear the gentle moaning of our refrigerator and freezer; there’s also the constant sound throughout the night of traffic trickling along an adjacent arterial road.

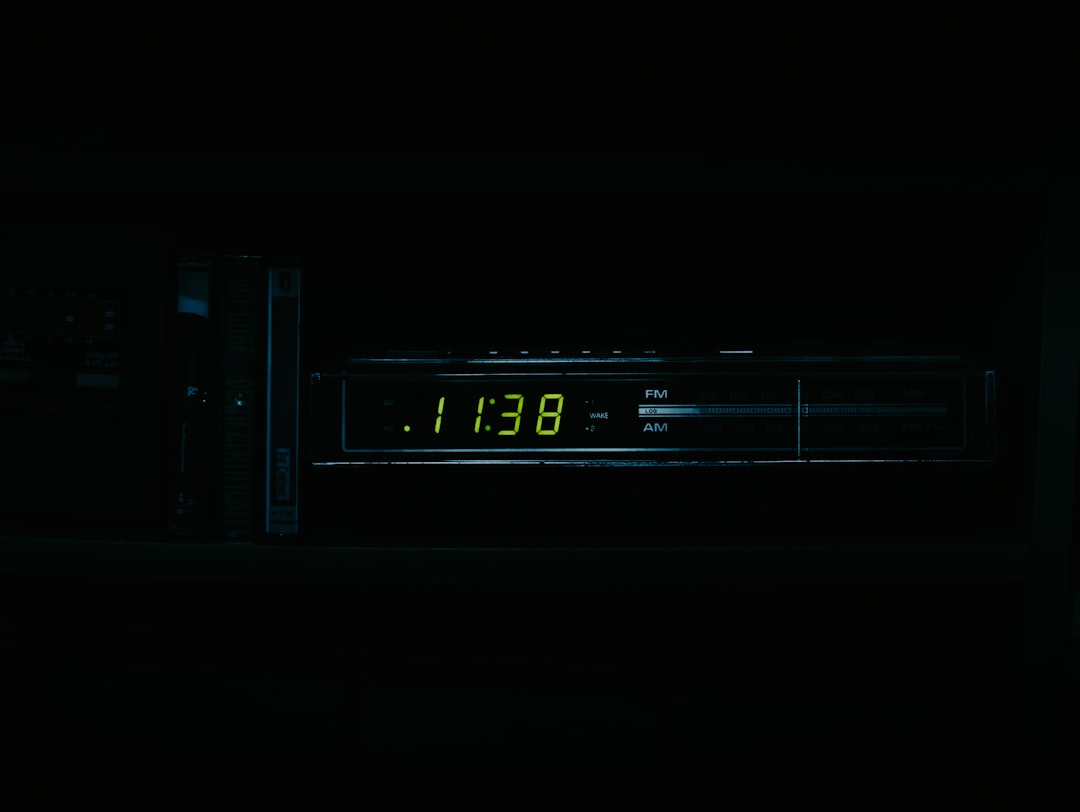

I awaken to darkness, but there is also light. My eyes open slowly, blinking at the green digits on my alarm clock screen. These cast a strange glow. And they are accompanied by other glows. A night light in our bathroom. The light we leave on all night at the bottom of the stairs. Perhaps there is also light shining faintly through the window — the moon reflecting off the snow — but it is lost in the miasmic fog of artificial illumination.

What is the effect of beginning the day in this way? I have rarely asked upon waking, “Where am I?”—although perhaps my body is asking the question as it creaks into the unnatural series of movements that constitutes our existence.

“Where am I? How did we get here?”

The existential quality of being “located” in time and place is surely more complex than simply knowing where things come from. Nevertheless, my experience of dislocation begins from the moment that the alarm starts to shriek. (We know that this is true because of how alarm clock manufacturers have begun producing alarms with more “natural” sounds such as birds or ocean waves. Ironically, the shriek—produced as it is directly through an electrical mechanism within the alarm rather than as a recording or digital imitation of a sound—may be ever so slightly more “natural”). The alarm dislodges me from my place in the world with a violence that is necessary lest I miss the window for entering the modern workday. Furthermore, although I typically beat the alarm and wake up before it begins to shriek at all, this training that has occurred in my body is one that continues even on days when I do not need the alarm at all.

To return to the room in which I find myself upon awakening, the experience of dislocation continues tactilely as I raise myself from my bed—a combination of mattresses and frames and cotton sheets and blankets. The origin of each of these things are all lost to me, having derived from a global supply chain whose complexity escapes understanding. My bare feet come to rest on a floor that was likely purchased at Rona or Home Depot sometime in the early 2000s, and perhaps at one time had taken the form of trees swaying on the ridge of some mountain, before being pulped into fibres and laminated together with synthetic glue, but again that history is lost.

Before I stand up, though, I should take note of something that repeatedly threatens to undermine this description of doomed solitude—this tale of the bereft and alienated modern person cast adrift in a sea of things. The threat (or promise) comes from the untold stories that adhere to all these things that my body bears witness to as I slowly emerge into wakefulness.

The floor may have come from some bigbox renovation store, and I cannot even tell what tree it was made from; however, there is an interesting story that cannot be dislodged from it and which, in fact, lodges and locates the floor within my own history in a more constant and ongoing manner than it might have otherwise.

When we purchased the home we live in just over 10 years ago, the basement was a mess. Linoleum sheets were stuck directly on the cement—or not at all. The main floor of the bungalow was a mishmash of different flooring. In the front living area, the previous owners had installed a dark, shiny laminate flooring that resembled hardwood (if only very slightly). Among the many changes we have since made to this house over the years, one was to move this flooring downstairs into our room. In fact, the full story is that my father-in-law did this for us, removing each piece of laminate from the main floor, leveling the subfloor in our basement room (which he also built along with my brother-in-law), cutting the pieces so that they could fit, and setting each piece into place.

My bare feet upon the floor feel something different as I recall this. Does gratitude alter our existential position?

These kinds of stories adhere to many of the “things’“ that surround me upon waking. I may not know who made my mattress nor understand the manufacturing process that went into the “memory foam” that we recently added to it; however, I do recall that the mattress itself was given to us many years ago by a coworker, who was getting a new one. He had inherited the mattress in turn from his father-in-law. This memory leads me to wonder whether it’s time we get a new mattress for the sake of our backs! Yet would it be possible to find something so capable of literally embedding us so deeply into our own lives? To have a mattress for 10 years and to know whose it was before, to be grateful for the gift of it, and to awaken aware of this care that was once shown to us (and continues to be): I’m not sure that Sleep Country can compete with that.

This entry has been an attempt to describe the ways I am unmoored even within the first few minutes after waking. Yet I find that I have not been abandoned. The tendrils of our uprooted selves press more deeply into the soil of existence and discover new sources of belonging in the form of story and gratitude. Nevertheless, these glimmers of hope should not distract from the direness of our situation. All manner of object and assumption conspire to knock us out of our creaturely track and on to a track of a more commercial nature. (Even if it takes the wailing shriek of an oscillating circuit). Story and gratitude have preservative powers, but a more active agent may be necessary to strengthen and buttress this fragile architecture.