This post was originally posted at my Brethren-focused website, O Brethren! I am not sure I currently agree with everything herein, but thought I’d repost here anyways — I’ll post new stuff as it comes up.

An aspect of Brethren history that has sometimes been overlooked by contemporary assemblies in my experience is its strong focus on questions surrounding prophecy. Specifically, many early Brethren writers and speakers held a fascination with the study of Biblical prophecy. This may come as no surprise given the role Darby played in the systematization and dissemination of a Dispensational view of history.

Tim Grass (author of numerous publications on Brethren history, including the definitive Gathering to His Name) writes:

Early on, the study of Bible prophecy became central to Brethren life; it was a respectable intellectual pursuit at the time, and Brethren became known for their distinctive approach to it, known as Dispensationalism (though this never achieved universal acceptance among them).

A vehicle for this interest in prophetic study was the series of conferences that were held annually in Ireland on Lady Powerscourt‘s estate in County Wicklow from 1830-1833 and afterwards in Dublin. Notably, these conferences — and the general interest in unfulfilled prophecy — did not originate with the Brethren (as Grass implies above); rather, it seems to have been part of the general Zeitgeist in nascent Evangelicalism. Powerscourt herself had attended a popular prophetic conference in Albury in Surrey, which took place between 1826 and 1830. (Tim Grass suggests that these Albury conferences were distinct in their view of prophecy from that held by Darby and other dispensationalists [Gathering 26n.98]). The Brethren emerge partly motivated by this intellectual current within Evangelicalism.

On at least a couple of points, this makes sense:

- Taking the Bible seriously was a position occupied by Evangelicalism in contradistinction to what was seen as a generally lax position taken by the Established Church. To take the Bible seriously meant at least partly to believe the Bible’s own claims about prophecy and to look for its fulfillment in the present day.

- Prophecy, as literary historians such as Ian Balfour have suggested, gains a certain currency during the Revolutionary period of the late eighteenth century. I would be interested to know if there has been any scholarly writing connecting this interest in and rhetorical use of the prophetic mode in writers such as William Blake and Percy Shelley with the prophetic study movements of Edward Irving, Henry Drummond, or the Brethren. Hopefully, I’ll have more on that in future posts.

So where am I going with all of this?

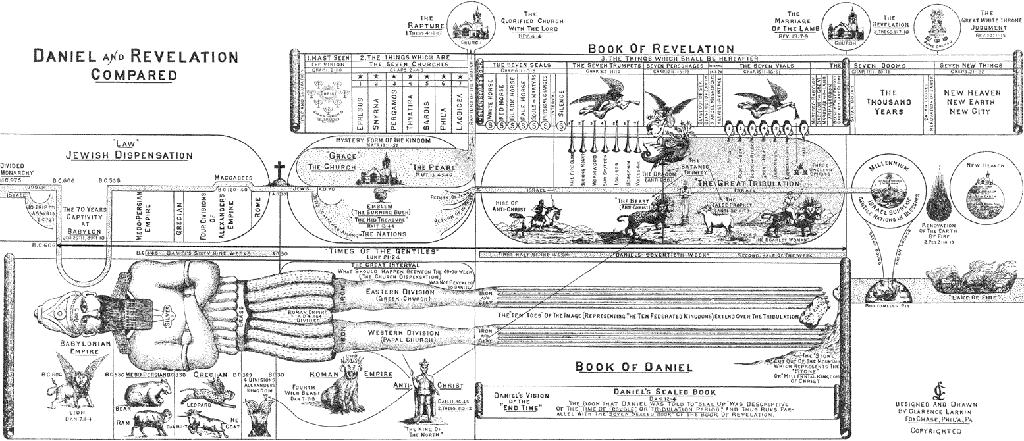

Part of what I have been finding interesting about researching the history of my own tradition is discovering the places where what I thought was sacrosanct turns out to be the result of a messier sort of back and forth. For example, based on my almost non-existent familiarity with the idea of “prophecy” (I say “almost” because of some rather quintessentially Brethren run-ins that I have had: i.e. my love of end-times fiction and non-fiction as a young person and my obsession as a kid over the timeline of dispensational history that hung in the hallway of the Bible School my grandfather helped start), I would have assumed that to be fascinated with prophecy would also of necessity mean a fascination with the other spiritual gifts. Yet a dominant thread in Brethren theology is a sort of soft cessationism, which sees the charismatic gifts as having ceased with the arrival of the New Testament. While this is not my own view and not (as far as I know) the view of the assemblies I have been a part of, it is a position that has been held by several major representatives of Brethren thought since near its inception (Grass 91).

What a closer look at the role prophecy played in early Brethren history reveals, though, is that there was a kind of openness to the supernatural — to the fulfillment of prophecy in particular — that was inflected by an “erudition” that is also one of the distinctives of the Brethren. It may be a bit of a weak analogy, but it makes me think of Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, a fantasy novel by Susanna Clarke. In that novel, the setting is early nineteenth century England. Magic used to be commonplace, but is now only studied theoretically. I don’t know how well that describes the situation in which Darby and others find themselves, but I find it helpful at least preliminarily. There doesn’t seem to be any question of modern-day prophecy being possible.

Yet it is also not accurate to say that their interest is only “theoretical”; rather, they come to this study with an expectation that Biblical prophecies could yet come true or that they have been fulfilled in history, but that this fulfillment had not been recognized.

Moreover, they seem to be regularly on the lookout for the movement of the Spirit. Grass tells a fascinating story about claims made around 1830 by followers of Edward Irving (another restorationist from the period whose views overlap with the early Brethren — even as they also diverge significantly). Grass writes:

Darby, probably accompanied by [George] Wigram, went in 1830 to investigate what was happening in the West of Scotland, where it was claimed that the gifts [of tongues and prophecy] had been restored; Irvingites and Brethren mixed at the early Powerscourt conferences; and some who had been influenced by Brethren later joined the Irvingite movement. (90)

So, right from the beginning the Brethren are interested in questions about how the Spirit is working in the present. There is certainly a skepticism and also a rationalism there that resists a more overtly charismatic understanding. I can only speculate as to the reasons for this, but I imagine that at least somewhat there is a role played by the individual histories of the earliest “chief men among the Brethren.” Darby and B.W. Newton were both scholars (as was Henry Craik). Newton’s Quaker upbringing — which he had rejected as an adult — had coloured his view of mystical experience (Grass 29). Yet despite the suspicion, there is an undeniable, ongoing and deepening attraction to the movements of the Spirit and this ultimately expresses itself in all sorts of interesting and innovative ways — including what Grass calls (after Ian Rennie) the “‘laundered charismaticism’ operative in such contexts as the Breaking of Bread, inspiring individuals to contribute to the worship” (Grass 91) and also, as I will explore in a subsequent post, the “faith ministry” of George Müeller and many other Brethren individuals and ministries, even up to today. Despite its uncertainty about certain charismatic gifts, the Brethren movement can, I believe, be quite justifiably claim to belong to the category of “Spirit-filled.”

References

Grass, Tim. Gathering to His Name: The Story of Open Brethren in Britain and Ireland. Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006.